Introduction

Most of the current produce safety-related regulations, certifications, and/or standards are targeted at medium to large produce operations. Small and very small growers are subject to a less strict set of food safety practices and often lack the resources or technical expertise to meet more stringent requirements. This includes the testing of agricultural water, which is used in activities where it is intended to, or likely to, contact produce or food contact surfaces, including during growing, harvesting, packing, and holding activities. Testing agricultural water can be costly and logistically challenging for smaller operations. Alabama has over 2,000 produce growers; however, most produce growers are exempt or not covered (total produce sales < $25K/annually) by the Food and Drug Administration Produce Safety Rule (PSR). Agricultural water has been previously linked to several produce-related outbreaks, as it is a well-known source of microbial contamination in horticultural commodities. Some horticultural commodities that have been impacted in the past include spinach, onions, and romaine lettuce (Food and Drug Administration C for FS and A; CDC, Multistate Outbreak of E. Coli O157:H7 Infections Linked to Romaine Lettuce (Final Update) | Investigation Notice: Multistate Outbreak of E. Coli O157:H7 Infections April 2018 | E. Coli | CDC; CDC, “Outbreak of Salmonella Newport Infections Linked to Onions | CDC”). Historically, some regions of Alabama, particularly the Black Belt, have been characterized by a lack of access to sanitation systems and a higher susceptibility to well water contamination (Winkler and Flowers). While most of the research and outreach efforts in Alabama have focused on drinking water, fewer have explored the microbial quality of water used for agricultural purposes. Hence, the AgWater Safety Program is currently supporting produce growers with food safety and water quality resources.

Materials and methods

Growers are recruited during food safety training and horticultural events (both virtual and in person). Additionally, flyers are also distributed at farmers’ markets, workshops, and conferences. Participants complete a Qualtrics screening survey to determine their qualifications for the program, which include using agricultural water sources for fresh produce during pre or postharvest. Growers enrolled in the program received a water kit free of cost. Generic E. coli is measured from water samples using the IDEXX Colilert with the Quanti-Tray/2000 method.

Results and Discussion

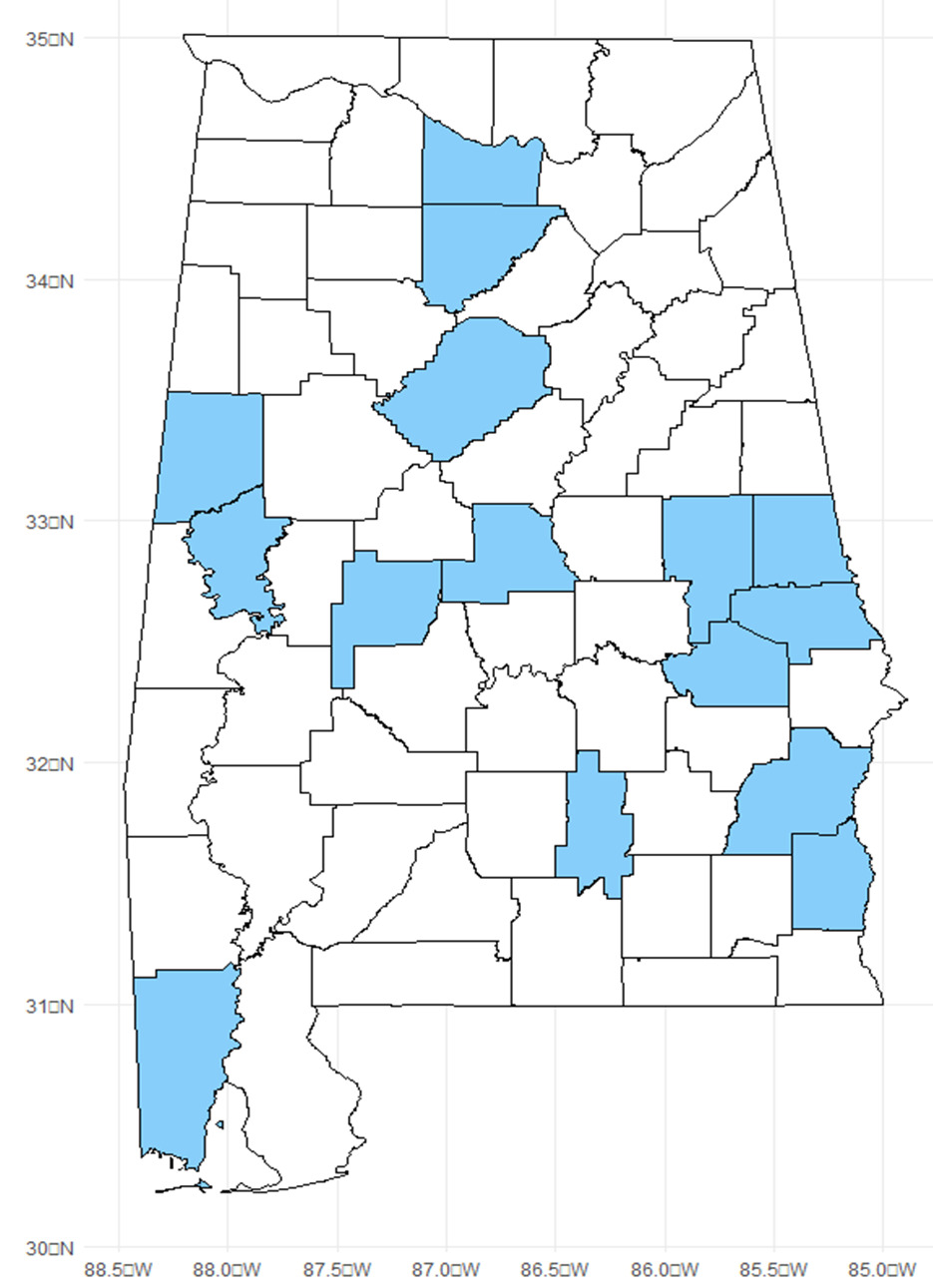

To date, the Program has benefited at least 20 produce growers across different counties in Alabama (Figure 1). Amongst the participants, there are various levels of farming experience; over 50% report having more than 10 years of experience. Figure 2 shows the main commodities grown by the Program participants. Additionally, the majority of participants self-reported selling less than $25,000, and only 20% reported selling between $25,000 – $500,000. Produce growers also reported selling produce at different points, including farmers’ markets, restaurants, and roadside (Figure 3).

Previous studies in the region have identified that a main concern for growers when applying food safety practices represents a financial burden (Vaughan et al.; Mohammad et al.). Considering that the AgWater Safety Program is free of cost, it is positively impacting the food safety practices for growers in the region. To date, eighty-three samples have been analyzed for generic E. coli and total coliforms from different water sources (Figure 4). Overall, E. coli was detected in 28% (24/83) of the samples. Within the analyzed samples, there is a higher prevalence of E. coli in the surface water, 58.82% (20/34), in comparison to groundwater 10.25 % (4/39) and municipal 0% (0/9). Surface water sources are well-known sources of microbial contamination due to their exposure to the environment (Gurtler and Gibson; Microbial Hazards in Irrigation Water: Standards, Norms, and Testing to Manage Use of Water in Fresh Produce Primary Production - Uyttendaele - 2015 - Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety - Wiley Online Library). In our study, the highest counts of generic E. coli (1011.2 MP/100 mL) were detected from a well, in which the well owner reported not using the well for years which might explain the elevated microbial count due to lack of maintenance. The higher loads of E. coli from surface water reached 920.8 MPN/100 mL, although is a high concentration it was an isolated event that could be attributed to collecting following a rainfall event. In Alabama, previous studies have evaluated surface and groundwater from agricultural experimental stations; however, no generic E. coli was found in groundwater; similarly to this study, the indicator organism was found in surface water (Gradl). In neighboring states, the presence of E. coli and pathogens like Salmonella has been assessed in horticultural operations and recreational water. However, neither Salmonella nor E. coli have been detected from well water samples (Antaki et al.).

The AgWater Safety Program offers significant benefits to growers by providing free water testing with detailed reports and empowering growers on to the importance of monitoring the quality of the water used on fresh crops. Growers can use these reports to identify potential contamination sources and take corrective actions to ensure the safety of their water supply. By addressing water quality issues, growers can reduce the risk of contaminating their fresh produce, thereby enhancing the safety of the crops they sell to local markets and school programs. This approach not only helps in meeting food safety standards but also builds consumer trust and opening new market opportunities for local growers. Ultimately, the program supports Alabama produce growers in producing safer, high-quality produce, contributing to the overall health and well-being of the community.

Conclusion

The AgWater Safety Program has benefited several growers in Alabama by developing agricultural water sampling educational material, workshops, field days, and free water sampling. The educational materials are published and available to growers at the Alabama Cooperative Extension System. More education and outreach are needed to incentivize produce growers to learn and implement food safety practices at their operations. Additionally, more collaboration is required to expand the program. Our findings reinforce the importance of assessing the microbial quality of water used for agricultural purposes in Alabama. Further studies are recommended to assess the prevalence of pathogens in water sources and, overall, on-farm practices to develop more programming around food safety needs in Alabama.

https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/farming/agwater-safety-program/

.png)

.png)