In recent years, there has been a growing agricultural trade imbalance in U.S.-China relations, with imports increasing at a faster rate than exports. Notably, China is the world’s largest consumer and importer of agricultural products. As figure 1 shows, China is projected to be the third largest partner in U.S. agricultural trade among individual countries, with an export share of approximately 16.25% and an import share of about 2.42%, following Mexico and Canada. This series of reports aims to be published quarterly, offering a comprehensive review of U.S.-China agricultural trade data. Each edition will also introduce a new agricultural product that shows potential benefits for our farmers, highlighting emerging opportunities in the dynamic trade landscape between the U.S. and China.

After the sharp increase in exports between 2020 and 2022, the export value went through a subsequent decline (figure 2). Since 2016, agricultural imports have shown a continuous upward trend, increasing from $121.1 billion to $202.5 billion. Agricultural trade between the U.S. and China, prior to 2019, was characterized by trade surplus – exports exceeding imports. However, after 2019, the quantities became very close, but a significant shift occurred in 2022 when the volume of exports was far lower than imports. The trade deficit is forecasted to worsen. In fiscal year (FY) 2024, U.S. agricultural exports are projected to reach $170.5 billion, and imports were revised upwards to $202.5 billion. This $1.5 billion increase in imports from the February projection is predominantly driven by higher imports of horticultural products, livestock, and dairy.

Overall trade trends

In the first quarter of 2024, agricultural trade between China and the U.S. fell by 32.8% to 11.02 billion USD (figure 3). This accounts for 11.13% of the U.S. total imports and exports. Among this, imports were 2.53 billion USD, an increase of 16.6% compared to the same period last year, marking the highest value in the past five years for the same period, ranking first among China’s agricultural export markets by country. Exports were 8.49 billion USD, a decrease of 40.3% compared to the same period last year, ranking second among China’s agricultural import regions by country. The trade surplus was 5.95 billion USD, narrowing by 50.6% compared to the same period last year.

Imports from China

In Q1 of 2024, tobacco and related products had the highest value of imports from China to the U.S. Tobacco and related product imports totaled 660 million USD, a 38.5% increase over the same period in 2023 (figure 4), which accounts for 26% of total agricultural imports from China (figure 5). Imports of aquatic and marine products and their derivatives amounted to 430 million USD, a decrease of 7.8% from the same period last year. Fish and fish product imports, which make up the largest share of this category, totaled 270 million USD, down 13.7%. Imports of vegetables and its products increased to 230 million USD, up 24.7% over the same period last year. This category accounts for 9.2% of the total imports of agricultural products from China. Garlic accounted for 110 million USD, a 44.3% increase from last year.

Exports to China

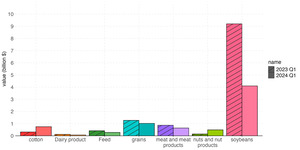

China does not have a comparative advantage in production agriculture, especially for land-intensive feed grains and proteins such as soybean and beef.[1] As a result, China accounts for over 60 percent of global soybean imports[2] and has been a major exporter of U.S. in soybeans, corn, wheat, and cotton (Figure 7 illustrates the percentage breakdown of each product the U.S. exported to China in the first quarter of 2024). In the first quarter of 2024, China imported $4.1 billion of soybeans from the U.S., a 57.4% decrease compared to the same period last year (figure 6). Soybean exports from the U.S. to China account for 48.4% of China’s total agricultural imports from the U.S.

Grain exports totaled $1.02 billion, a 19.8% decrease. Different grains exhibited different trends, with sorghum exports up 879.4% and totaling $630 million; corn exports down 76.9% and totaling $260 million; and wheat exports up 63.9% and totaling $130 million.

Meat and meat product exports totaled $640 million, a 26.3% decrease compared to the same period last year. Beef, pork, and chicken products were all down over that period by 4.2% to 60.0%. Notably, the U.S. increased cotton exports to China by 136.4%, to a total of $750 million in 2024 Q1.

Which states import the most agricultural products from China?

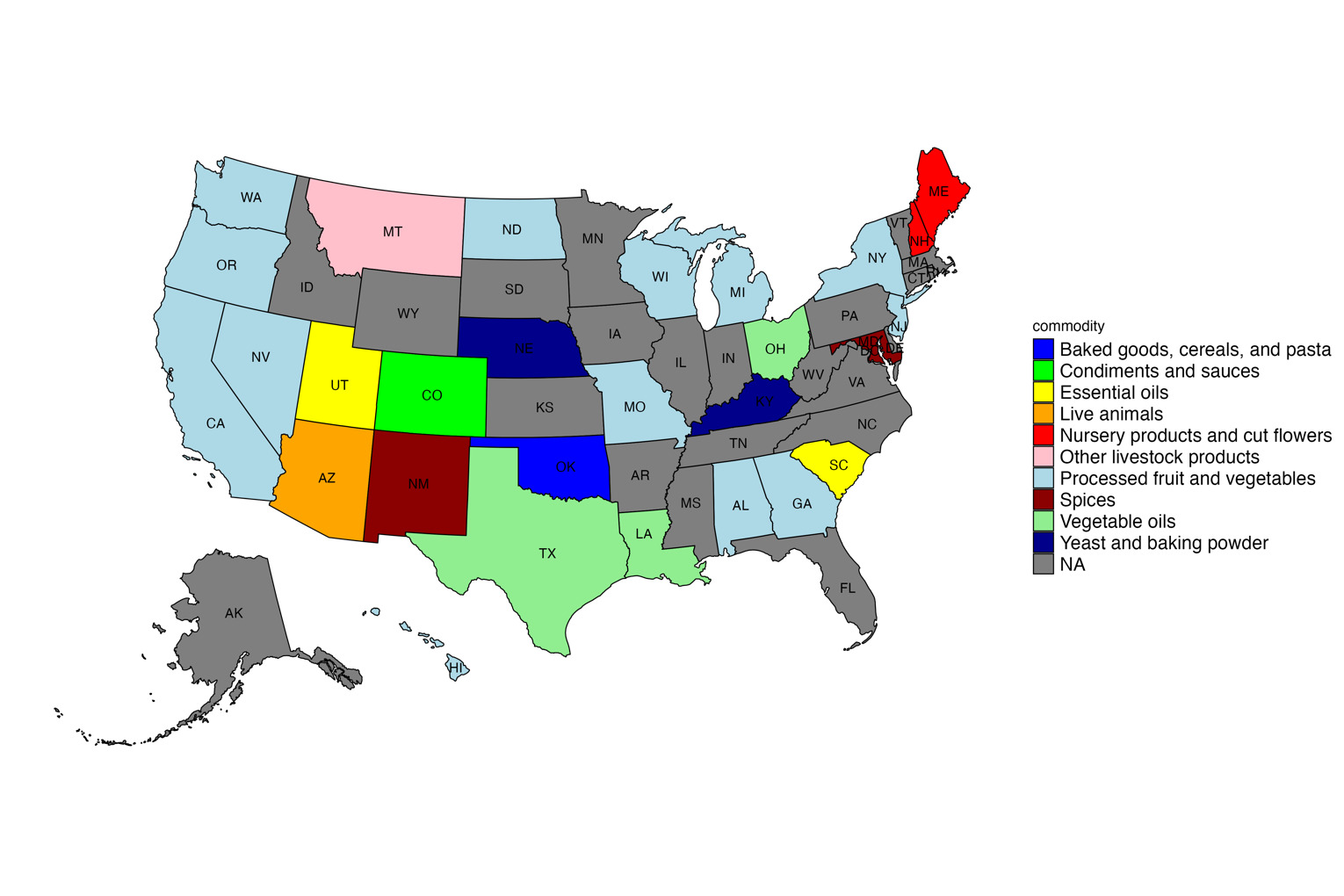

The top 5 states by import value are Texas (TX), California (CA), New Jersey (NJ), New York (NY), and Georgia (GA), which primarily import vegetable oil, processed vegetables and fruits, and fresh fruits.

In the first fiscal quarter of 2024, 28 of the 50 US states had imports from China. Texas imported the most vegetable oil, valued at $290.30 million. California imported the most processed vegetables and fruits, and fresh fruits, valued at $82.59 million and $19.64 million, representing 2.8% and 55.3% increases from last year, respectively. New Jersey, New York, and Georgia followed, importing processed vegetables and fruits valued at $41.04 million, $22.48 million, and $15.86 million, with year-on-year changes of 18.6%, 13.2%, and -35.6%, respectively.

Which states export the most agricultural products to China?

The top 5 states by export value are WA (Washington), LA (Louisiana), CA (California), VA (Virginia), and IL (Illinois). They primarily export soybeans and tree nuts.

Among 50 states, 41 states export agricultural commodities to China. Washington (WA), Louisiana (LA), Virginia (VA), and Illinois (IL) export the most soybeans, valued at $3.49 billion, $2.77 billion, $0.32 billion, and $0.30 billion, respectively, decreasing 27.75%, 42.53%, 44.46%, and 42.10% year on year. And California (CA) exports tree nuts, with a value of $0.70 billion, increasing by 109.97%.

In the first quarter of 2024, twenty-four out of the thirty-one Chinese provinces and municipalities increased agricultural exports to the U.S. compared to the same period last year, while twenty-six increased U.S. agricultural imports.

Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu are the top three destinations for American exports in China (figure 10). Exports to Beijing amounted to $2.36 billion, a decrease of 24.8% compared to the same period last year, accounting for 27.8% of total U.S. agricultural exports to China. Exports to Shanghai totaled $960 million, down 47.2%. Exports to Jiangsu Province were $930 million, a decrease of 51.4%. Exports to 12 other provinces and municipalities, including Tianjin, Hebei, and Guangxi, saw year-over-year declines of over 50%.

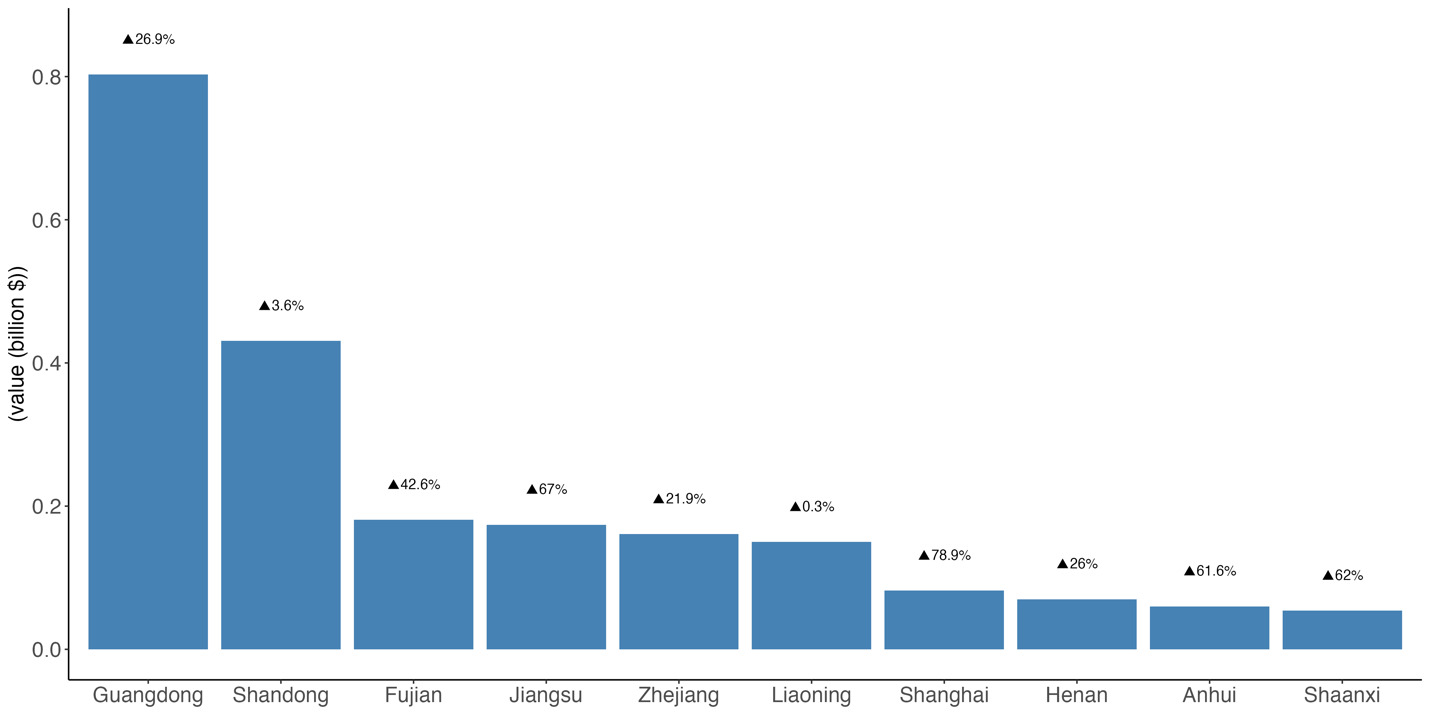

The top three destinations for agricultural product exports to the U.S. were Guangdong, Shandong, and Fujian (figure 11). Guangdong led the way with an export value of $800 million, a 26.9% increase compared to the same period last year, accounting for 31.7% of Chinese agricultural product exports to the U.S. Shandong had an export value of $430 million, a 3.6% increase, accounting for 17% of the total; Fujian had an export value of $0.18 million, a 42.6% increase year on year, accounting for 7.2% of the total.

New Trade Opportunities: Spotlight on Alfalfa

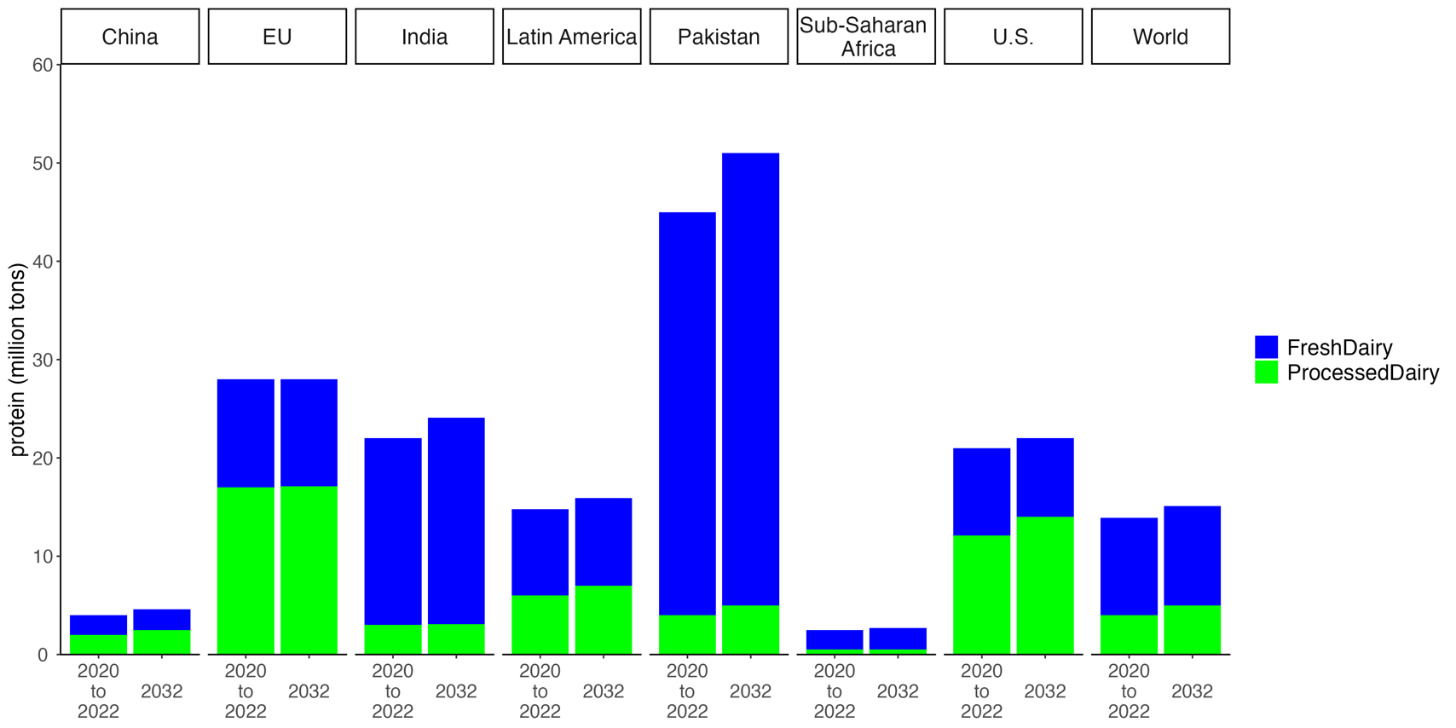

Considered the “king of forage,” alfalfa is a high-quality forage crop critical to food security worldwide. With the increasing global consumption of meat and dairy products, alfalfa plays an even more significant role. As income and population increase, dairy consumption is expected to grow. As shown in figure 12, countries like China, India, and Pakistan are expected to experience the strongest growth. Globally, per capita consumption is expected to increase by 0.8% annually, reaching 15.7 kilograms in 2032 (measured in milk solids, excluding water content in milk or dairy products). This figure represents a per capita amount; given China’s large population, the total increase in consumption is substantial. Compared with developed countries’ preference for processed dairy, developing countries prefer fresh dairy. China, with its rise in demand for meat and dairy products, possesses a considerable demand for alfalfa. While the demand is enormous, slow developments in China’s domestic alfalfa industry have limited its ability to satisfy demand, such as limited land and water and the lack of experience in managing alfalfa as a commercial forage crop. These limitations include an external dependence rate of alfalfa hovering at 35% for a continued period, considerable reliance on imports, declining in the production of alfalfa that meets higher quality standards, nearly 80% of seed volume dependent on imports, and a large demand gap in general.

When comparing the alfalfa industries of China and the U.S., it is evident that the U.S. holds a significant competitive edge in key areas such as seed breeding, planting, industrial development, and competition patterns[3]. While China’s breeding subjects are relatively simple, the United States has established a robust system of breeding institutions and enterprises. The U.S. also leads in alfalfa planting trends, which are similar to hay and exhibit stability, unlike China’s more fluctuating and declining trends. In terms of industrial development and competition patterns, the U.S. has built comprehensive industrial chains for seed breeding and production, planting, harvesting, processing, and consumption. It also boasts the most advanced grass seed industry globally, with three American companies leading the way in global alfalfa production.

As the world’s largest producer and exporter of alfalfa, the United States plants approximately one-third of the total alfalfa area in the world and has the highest alfalfa production in the world. As of 2022, the United States produced 48 million tons of alfalfa, with a harvesting area of 14.9 million acres. Furthermore, 1.68 million acres of new alfalfa seedlings were planted, demonstrating the U.S.'s robust alfalfa production system.

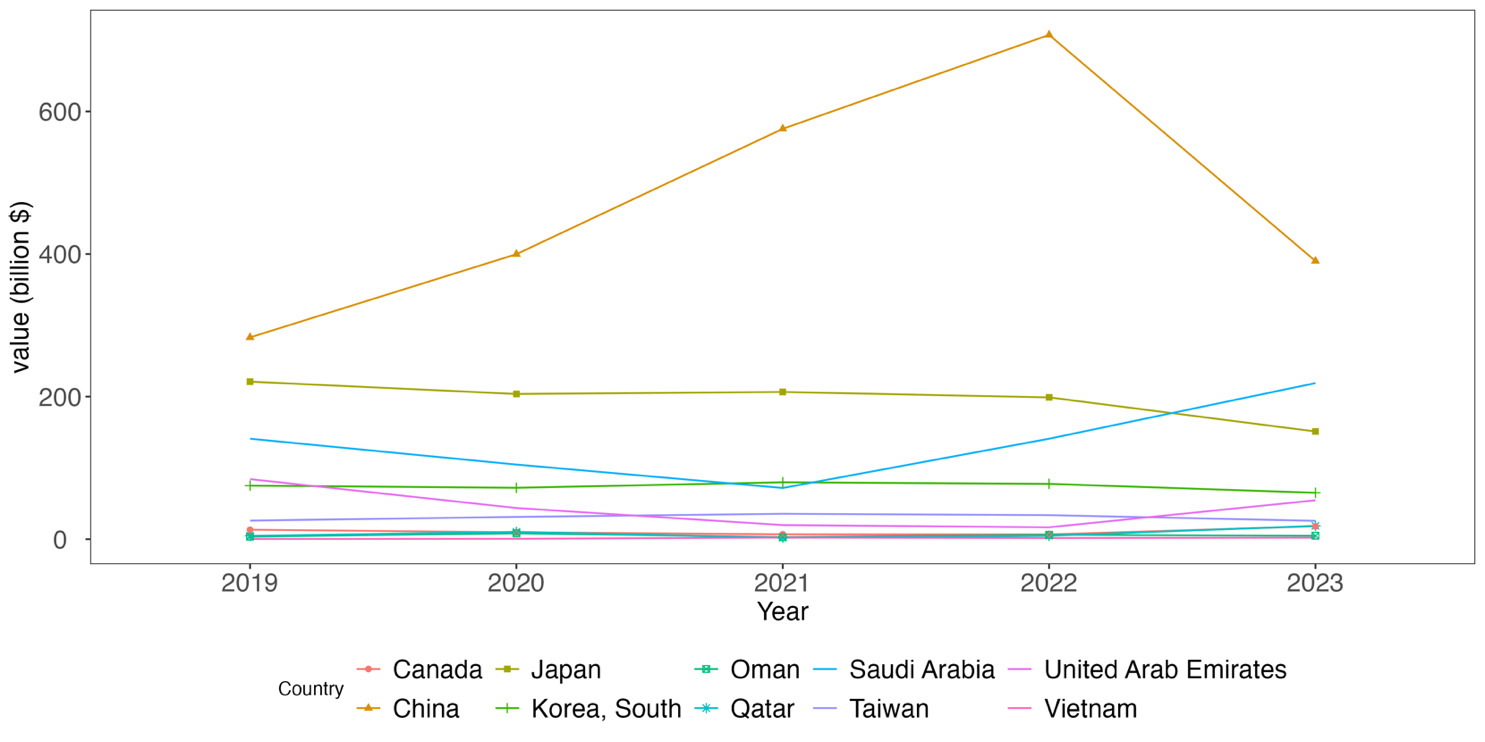

The U.S. primarily exports alfalfa to China, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. As shown in figure 13, China has been the largest importer of alfalfa to the United States for five consecutive years, showing a large potential market. The U.S. is China’s largest import partner for alfalfa, with notably high quality[4], followed by Spain and South Africa (figure 14). To meet China’s growing demand for alfalfa, some policy recommendations include improving product quality control by placing more emphasis on certification, such as for National Organic Program (NOP) standards[5] and non-GMO certifications. Due to China’s cautious approach towards genetically modified crops and the slow approval process, the import of genetically modified alfalfa was only relaxed in 2023. Additionally, as the demand for organic dairy products increases in China, the demand for organic hay is also expected to rise in the future, with organic alfalfa likely to command a higher premium compared to conventional alfalfa. Moreover, since technology is a key factor restricting the development of China’s alfalfa industry, more technical support and services must be provided.

Conclusion

Despite a slight decrease in trade volume between China and the U.S. in the first quarter of 2024, China is and will continue to be one of the most important trading partners with U.S. agriculture. To enhance the export, the government should encourage the cultivation of agricultural products where it holds a comparative advantage and which have strong demand in the Chinese market, such as grains, nuts, and so forth. With the transformation of China’s dietary structure, there is a significant increase in demand for dairy products, indicating alfalfa will have tremendous trade potential. In conclusion, despite the current trade pace with China, it is crucial to forecast the dietary structure and resource endowment of developing countries with large populations and rapid economic development, like China, to fully tap into its trade potential.

As Wendong Zhang mentioned in “Seven things to know about China to understand the trade war”, comparative advantage, which refers to the ability of a country to produce a product at a lower opportunity cost than that of trade partners.

Gale, F., C. Valdes, and M. Ash. “Interdependence of China, United States, and Brazil in Soybean Trade”, OCS-19F-01 USDA, Economic Research Service

Victoria D. “People’s Republic of China Market Overview - Alfalfa Hay and Other Forages.” 2024, USDA, Foreign Agricultural Service

As mentioned in “China’s Alfalfa Market and Imports: Development, Trends, and Potential Impacts of the U.S.–China Trade Dispute and Retaliations” by Qingbin Wang and Yang Zou (2020), the U.S. accounted for an average of 97.01% of China’s alfalfa imports between 2007 and 2017.

As mentioned in “Producing Alfalfa Hay Organically” R.F. Long, R.D. Meyer, and S.B. Orloff (2008), Growing alfalfa organically can be quite challenging as compared with conventionally produced alfalfa hay under strict regulations.

_between_the_u.s._and_china_from_2023_q.png)

.png)

_between_the_u.s._and_china_from_2023_q.png)

.png)